|

|

DROP YOUR DETAILS IN BELOW FOR NEWS AND PROGRESS UPDATES

Storytelling is a fundamental component of all indigenous cultures and heavily intertwined within their native educational systems. For Mentawai, according to Sikerei, “Our stories teach us about our history and how to survive here. They carry the wealth of Mentawai through the generations. This is our fortune.”

Over the years I’ve documented a variety of these cultural tales and edifying conversations – some of which you will see in the film. Given the immense historical value of these – for both present and future generations – I’d like to begin sharing a selection here too.

In this video Aman Masit Dere is explaining to his grandson, Jumer, the cultural guidelines to follow for protection when building an Uma (home) for his own family. Which, traditionally, is a significant milestone and rite of passage reached during a Mentawai lifetime – particularly for those seeking to become Sikerei.

This post/video is also available in bahasa Indonesian language here. Enjoy.

We plan to commence work on the Suku Mentawai program before the end of the year. However, to do so, we need to raise initial funding through IEF.

If you’d like to win this certified limited edition (artist proof #1) photo of native Mentawai – framed, be in the running by purchasing a raffle ticket for $2 each or $5 for three.

Tickets can be bought direct from an IEF representative or otherwise online by donating the desired amount via the foundation’s donation form here (which is paypal secure). Include the word ‘raffle’ in the comments box.

Also, if anybody is interested in volunteering some time to help sell a few tickets – perhaps within their own workplace – we’d be most grateful, as IEF is extremely limited in human resources at the moment. Contact us here.

The winner will be announced Oct 28th through the IEF news feed and IEF facebook page, so please sign up and follow along.

Thanks again for your support.

What might you wonder if you found a species of plant now struggling to survive in the exact same location it had flourished in for thousands of years – even after being provided a variety of enhancements to help it grow? …‘What is it that has suddenly caused this change?’ perhaps.

Over the past six years I’ve been researching and documenting the comparative behaviours and attitudes between resettled and non-resettled indigenous Mentawai peoples. This arising after identifying a profound and disturbing contrast between those who’ve maintained cultural belief and practice and those now detached from it – citing a notable shift from wealth to poverty.

Teaming up with local members of the community whom I found active in their ideas or initiatives to help prevent this demise, we gathered and analyzed research, established findings, and over the years designed and developed steps for implementing a preventative solution: the Suku Mentawai ‘Cultural and Environmental Education Program’ (CEEP).

In need then of a means to facilitate the CEEP’s implementation evolved the Indigenous Education Foundation (IEF). Which, beginning with Suku Mentawai, is aimed at supporting the development of a series of programs tailored to suit the specific wants and needs of indigenous communities around the world who are suffering the ruinous impacts of displacement.

Committed to keeping each solution local we also established a Foundation in Indonesia to implement and operate the Suku Mentawai program through. The native Mentawai engaged during the research period, who initiated and will subsequently manage the CEEP at a community level, are head of this Yayasan.

So here, now, finally, after many years, it is with a great deal of excitement that I present all of this to you. For IEF visit www.iefprograms.org. For Suku Mentawai, which is available in either English or Bahasa Indonesian language, visit www.sukumentawai.org (or just click through from one of various links on the IEF site).

The plight of indigenous people and their displacement from native lands, customs and education is perhaps the most controversial issue of the past century and the repercussions continue to haunt the world today. Yet despite all the attention, an effective solution has not been found.

This is not to say that what I present here is the almighty savior and immediate answer to all these problems. Not at all. In fact if the road thus far is anything to go by I’m quite certain a great many more years of challenges, revelations and developments are in store before ever even entertaining the mere possibility of such a thought.

What I do believe though is that this unique opportunity we have to build upon, founded through the incredible access and insight given by the indigenous Mentawai community, is real. This is their voice. Their solutions. If it’s not wanted then it doesn’t go ahead. If it doesn’t work then we learn and move to the next. This is their responsibility and they must take ownership – the opposition to displacement. And this, in my view, is the basis for a solution worth supporting.

Please read, comment, support, share and explore the many ways you too can become involved in helping turn these community goals into reality. Thanks again to all those who’ve given their support throughout and continue to do so. None of this is possible without you. Masurak bagatta.

Ps. I haven’t forgotten about the film. I hope to have more time now to work on securing a team and pursuing funding and distribution options to complete and release. Appreciate your patience.

Continuing on from recent articles discussing how the indigenous Mentawai community deals with illness and loss of life, I’d like to delve a little deeper into the practices of traditional Mentawai medicine; those who are trained to administer it; and the impacts caused by an increased lack of community access to it.

Firstly, it‘s worth mentioning that traditional medicine has been developed and depended upon by the Mentawai for thousands of years. It wasn’t until as recent as 1901 that the first missionary (August Lett) arrived; and 1954 before introduction of the nationalized programs designed to ‘integrate the tribal groups into the social and cultural mainstream of the country’ – shortly after Mentawai became a part of the Indonesian State (1950).

The origins of Mentawai medicine in fact date back to the arrival of the very first Sikerei. Which, perhaps reflective of the wisdom and foresight of their forefathers, is said to have come in the way of a young child named Simaliggai. As ancient mythology goes, Simaliggai possessed an intimate connection to the forest – the child knew how to hunt, gather, grow, heal, preserve and maintain peace within. Naturally, everyone wanted to know how to did this.

Simaliggai, taking advantage of this fortune, decided to teach this knowledge to others and, in doing so, formulated a way of being called ‘Kerei’. Whereby, following in Simaliggai’s footsteps, everybody who learnt these Kerei skills would also become educators – devoting their life to teaching, healing and protecting others. Which, given this quickly became the most aspired role in traditional Mentawai society, does offer some insight into the origins of cultural values and success in sustaining their existence.

In essence Sikerei are the backbone of Mentawai culture and sustainability – the societal figure the entire community turned to for healing, guidance, comfort, reassurance, protection and safety. Providing medical services is certainly one element but it’s fair to say that it goes a lot deeper. To give context, I thought I’d share with you an interesting excerpt on Community Health from the indigenous Mentawai Community Research Report document:

Access to health care on Siberut Island has not altered since 1998 when Cheeseman and Kramer conducted the health research study ‘Incidence of Illness Among the Mentawai People of Siberut Island’, as their description of the island’s modern health care facilities remains valid: ‘Currently there’s only one (operational) government-run community health clinic (puskesmas) in each of the two district towns, Muara Siberut and Muara Sikabaluan. A Puskesmas has been built in each of the PKMT villages (over 60 settlements) throughout the island but, with medical staff concentrated solely to the two district towns, none of these have really ever been operational’.

Meaning that, for all residents of communities located in the interior or on the west coast of Siberut – whom due to financial restrictions are seldom able to afford the cost of transportation to these district towns – they are effectively unable to access these modern health care services.

In spite of this, findings show that the general level of health within the Matotonan community remains high, as not one person canvassed during the baseline survey cited health or access to medical assistance as being an issue or barrier to their existence here.

A possible reason for this finding could be attributed to the presence of Sikerei. Whose role, as confirmed through qualitative data by 80.6% of all other demographics, is ‘to treat, heal, and protect the people’. This meaning that, if Sikerei are fulfilling the role as a community doctor, then the Matotonan settlement – where there’s found to be around 1 Sikerei per 35 residents – actually possesses Siberut’s highest ratio of doctors per capita.

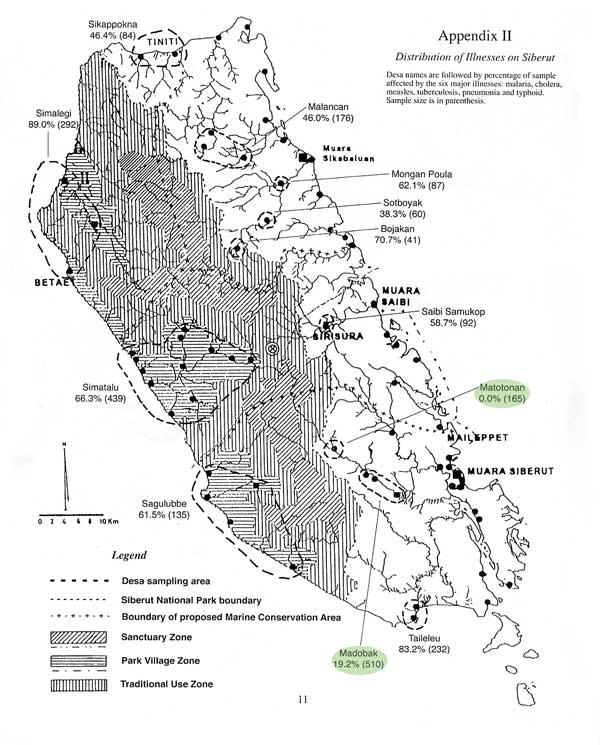

Adding weight to this is the data gathered by Cheeseman and Kramer during their aforementioned health report, which sought statistics on the proliferation of six major illnesses found on Siberut Island – malaria, cholera, measles, tuberculosis, pneumonia and typhoid.

As seen in figure 1.3 below, when focusing on the region where almost all the last remaining Sikerei actively practicing traditional Arat Sabulungan culture are located, of the 165 people canvassed by the pair in Matotonan there were no apparent cases of illness. Whilst in Madobak, the only other village surveyed for the report within this particular region, a mere 19.2% (of 510 people) reported having been affected.

When comparing this against all other settlements throughout Siberut these figures are considerably low. Which, coupled with findings showing 98.6% of the community would prefer to use traditional medicine administered by Kerei if they were to become ill; and that 77.1% believe that the community would not survive without medical attention provided by Sikerei, strongly suggests that the presence of an adequate number of trained Sikerei continues to have a significant impact on disease control and overall community health and wellbeing.

This is not meaning to take away from the benefits of modern health services here. Not at all. We know, with reference to the previous article, that these do save lives. I’m sure Aman Masit Dere and his extended family’s eyes are far more open to it as a secondary solution now too. But the reality is that this option – for many – is just not feasible. So my view, based on these findings, is that supporting the preservation and practice of indigenous healing as an alternative does deserve serious consideration here, as oppose to suppression.

Interestingly, listed in the Government’s ‘Plans for Improved Health Care on Siberut’ (1995-2000)(PHPA 1995 p.200) was an objective to ‘Establish a local connection through dialogue and training with Kerei’. Which, in detail, stated plans for the ‘establishment of dialogue between modern health care workers and traditional medicine men (shaman/kerei) with regard to frequent diseases, their treatment and prevention, and upgrading effectiveness of Kerei in basic first aid; particularly in areas not frequented by mobile policlinics’. Unfortunately this objective was never pursued.

It’s not much (compared to tradition) but, with Sikerei permission, I’ve begun documenting certain aspects of their traditional medicine on account that one day future generations of Mentawai may once again reestablish connection to its significance and relevance to their long-term health and wellbeing.

During the forage for medicine shown in the photographs throughout the article, which was required for severe stomach pains, Aman Alangi gathered the following plants (Mentawai dialect): Sipeupeu, Palugarejat, Simuinek, Laipet, Sarasarak, Sipukole, Pelekak, Simakkainauk, Gozo, Sipukairabik, Alutuet, Pasisikuk, Tarasilalu, Pasisingin, Simamait, Muttei, Pugetta, and Pukatutup.

Thanks for reading and stay tuned for an exciting announcement over the coming weeks. Cheers.

To reveal a little more of what this project hopes to achieve and to give those interested in supporting its cause a chance to do so, I’m launching a two-week fundraising campaign selling t-shirts to raise money for the not-for-profit indigenous education initiative.

To see the entire range of men’s and women’s t-shirt designs and to learn exactly how you’ll be helping indigenous peoples all around the world by purchasing one, please click on over to chuffed.org/project/ief.

Thank you for your support.

As Worlds Divide has been approved by the Documentary Australia Foundation as a project suitable for philanthropic support and is now provided fiscal sponsorship. Meaning any financial support given toward the project’s completion will be fully tax deductible here in Australia. Which, given the ‘real damn close’ stage the project is now at, could prove somewhat beneficial. You’ll find the film listed here on the DAF website. Good day.

Each time I return to Mentawai I discover something new about the people and about the way they deal with the often-confronting circumstances that arise during their lives. This recent experience presented all that and more.

Arriving in the port town of Siberut, Arla and I were greeted by news that my friend Aman Masit Dere was ill. His condition though was unclear. Infection. Leg injury. Fever. Confused, we purchased a variety of basic medical supplies to take up river.

His son, Aman Jiji, who had received word of our arrival, appeared late that day to collect us. He informed us that the illness was cough related; that he had been crook for over two weeks; and that at times he had been coughing up blood. He didn’t have a name for what this illness might be. We left at first light the following morning. The canoe ride takes eight hours if the river is not too dry.

To give you a sense of what eventuated here and in the days ensuing I thought I’d share with you some sections of writing taken from my personal daily musings:

Heading up river I enquired the whereabouts of his brothers. Aman Jiji responded, “Most of the extended family is at the Uma so that if he dies they can be there with him.” He then asked, smiling with incredible sincerity, “If my father dies will you still come to visit us?” He then quickly moved on making comment on a completely unrelated matter. All smiles. It is quite amazing to experience – first hand – the way they deal with what appears to be a life-threatening situation. Adopting this approach, I’m trying to give as little thought as possible to what may or may not be. The forest is soothingly beautiful to watch pass by.

Aman Masit Dere is terribly ill. My heart fell away when I saw him. He can barely move. This powerfully strong-willed man is frail and hurting. He has barely eaten for two weeks. I feel sick. Sitting with him, watching his daughters holding him upright and, in small green leaves, catching the bile he continues to cough up, tears wanted desperately to well in my eyes. I held it back. Arla was unable. They were quick to comfort her “You can’t cry. He is not dead. He is still strong. We need to be happy. We can’t confuse him.”

Five Sikerei were completing the final day of a Mentawai healing ceremony. We shared in the experience. They then asked for my advice. I suggested we take him down to the Puskesmas (medical clinic) in the port town as soon as possible. They don’t have any money. We will cover the costs. They agreed that, tomorrow, after completing the ceremony, we take him down river. I later managed to find some time alone. I cried for my friend. I will look into trying to extend my visa to stay on. Stay by his side.

Aman Masit Dere almost passed away last night. He coughed an incredible amount and found it very difficult to continue breathing. We’re now in the Puskesmas. It was a long, slow commute down the river. He was in the arms of his siblings or children all the way. He is connected to a drip and has a breathing apparatus stuck up his nose. He looks too exhausted to show any fear for this foreign environment. We have set up camp in his room. Ten of us. Including his three youngest children. I’m moved – even more so than previously – by the love and support shown by his family. Such a powerful form of medicine. So tired.

Long night. Breathing apparatus finishes its cycle every 40min so I need to switch it off then on each time. His drip control may have been tampered with and the first bottle was consumed too quickly. The second had stopped working by 5am and he was boiling up. There is nobody about so I have to locate and replace this myself. It is now 7.30am and he is in a lot of pain. The cough is killing him. Literally. The doctor should arrive in an hour or so to conduct tests. We wait. Watching his three youngest play and laugh on the other side of the room is a comforting respite.

It appears we won’t know results until tomorrow morning. We have also been warned about the contagious effects of Tuberculosis. Which is what they suspect he has. This is a real concern when considering how close his family, including his young children, have been with him over the past few weeks. And no doubt will be in the coming. We too are at risk. Sleeping alongside him. Caring for him. I’d say we’d have had the vaccination though.

Still in the Puskesmas. Masit Dere is showing no improvement. Eating. But very little. Something rather unique occurred this afternoon. Sitting by the bed I noticed him start to say a few things. As one might do in their sleep. Though only moments ago he appeared awake. Soon enough he was talking. Very quietly.

His daughter, son and brother noticed too and quickly came to his side but without saying a thing or touching him they listened closely. Intently. I could see tears fill their eyes as they crowded around. For a small moment I thought he had fallen into a state of confusion. Dissolution. Perhaps nearing death. My stomach tightened as though it wanted to rid itself of air. I quickly settled myself and watched on. It had to be a visual. A conversation with someone from a past life. This is common to the role of Sikerei. And, as I’m later told, to the circumstance of being severely ill.

It was a good dream, they reported. Having another Sikerei, his brother, and others present helped to ensure he followed the right path. The path to recovery as oppose to that leading him to death. They seem more positive now.

Shortly after this Masit Dere came to and called me to come close to him. He spoke. The conversation was intense – trying to juggle concentration on hearing him, understanding him, and processing the seriousness of the circumstance with regards to what he was saying. An incredibly powerful moment. In many ways life changing. I don’t think I’d realized just how much I meant to him and his family. This conversation will stay with me forever.

Doctor, or nurse, I think, has informed us that yesterday’s sample wasn’t clear enough. They’ll need to do another. The family are getting very agitated. They don’t like it here. They’re not seeing any improvement with this medicine. They want to return to the forest. “If he shall die it must be in the forest. Not here.” “You tell us what we should do. If he dies that’s ok, not your fault, but we don’t like it here.”

I’m advising we stay at least until tomorrow to find out what the illness is. I’m quietly confident he will be feeling stronger by tomorrow too. He has been eating a little more each day and has been on the drip for three days/nights now. I hope it’s soon though. This place is filthy. There’s already lot’s of itching and coughing going on. And now all the kids have some kind of flea in their hair.

He is feeling a bit better today. He was up coughing a lot last night but he is getting his strength back. Results arrived. He has Tuberculosis. Which is curable. They’ve given us three weeks of medicine and he’ll have to travel to the nearest resettlement village for more each time he runs out. It’s a six-month packet.

Thankfully we are moving out of the Puskesmas and back to the community’s social accommodation house by the river. My visa expires tomorrow. It is too soon to leave him. We will make enquiries about getting my passport to the mainland.

All fell into place. Masit Dere feeling stronger again today so we head back up river. What a moment arriving to the Uma. His second eldest daughter, Liana, who has been looking after the other children whilst we’ve been gone – including two of her own – has been running to the river for every canoe she hears approach. She‘s had no word of our whereabouts or about his condition. We’ve been away for five days.

Finally she sees that it’s us in the canoe. Their faces. The tears. The joy. Their father is still alive. Wow. It is truly amazing when life presents a scene of such raw happiness. So glad to be back here. Everyone is feeling the same. We spend the evening singing and talking and drinking tea and laughing. It feels a lot more like the evenings I’d become accustomed to.

Masit Dere grew stronger each day. By the time we left to head back to Australia he was eating well. The passion for life had slowly begun to return to his face. He now participated in conversation; projecting his customary spiels and tone that would lead you to think he’s arguing the world’s most important issue when it is in fact merely a discussion about collecting timber to build a new contraption. He has agreed to stay off the tobacco for the next few years at least and, I think, grasps the importance of needing to take the medicine everyday for the entire six-month period. It was an emotional departure.

I guess the reason I felt this important to share relates back to a recent article I wrote discussing the methods by which the Mentawai community here deal with illness and loss of life and whether this contrasts against what, if any, actions need to be taken. This experience, coinciding with this effort to determine what is best for the community with regards to their situation, has indeed broadened but yet refined my views.

In particular, it has further highlighted the people’s positive attitude for accepting death as a natural form of life and that, despite the consequence, they feel safer within the confines of the environment they know and trust. But equal to this they do not want members of their family to die. And in cases such as this, which are quite common amongst these remote communities where they’re unable to afford costs for any other option, it’s possible that these deaths are prevented with minimal disturbance to their desires.

I’m unsure of the costs that would be involved in such an exercise, but, given what I know about the people and have learnt from this experience, it seems the most logical step would be to provide early immunisation against life-threatening and contagious diseases such as Tuberculosis. A simple vaccination. A needle given to each person within the comforts of their nearest village. I believe this would have almost no impact on their ongoing perceptions of survival here, but would most definitely save lives.

With regards to action, the program and foundation being developed as part of this project focuses more on education than specific medical health issues such as this – there are other experienced organisations that focus their work in this field. However I am eager, on the side, to further research the possibilities of working with others to help make this happen. So I ask, if any readers have access to experience, contacts, facilities, or just general advice with relation to helping achieve this, please make contact.

Whilst I don’t yet know much about the procedures involved in vaccination, I feel it would be foolish not to explore these pathways which arise that are ultimately leading to the one desired outcome for the livelihood of the Mentawai people. Thanks for reading.

Certainly not setting any records for the pace that this project is developing at but I can assure you it is progressing and I am getting closer and closer to announcing a few rather exciting advancements. Meantime, here is a photograph of a Mentawai Sikerei attempting to take a photograph of me.

Infant mortality is indeed a sensitive subject and, for all things related, difficult to know how best to approach when discussing on a public platform. My dilemma, after having observed an unexpected sense of functionality in a people coping with losing what I’d consider to be an abnormally high number of infants, is that as a result of this I find myself now questioning exactly how to react.

In a study conducted in Mentawai in 1978 by Hólfer and Pech, it was found that between 15-24% of women lose a child under the age of five. Which, when compared to most developed countries, is an extremely high percentage. In a study we conducted within remote forest communities here in 2011, it was found that for these women the figures have not improved. Thirty-three years on and still around one in four women here will lose a child under the age of five.

Naturally, upon learning of this situation, the mind quickly leaps to the theory that if we share our modern advancements in medicines, health services and facilities, we can help prevent these deaths and improve the lives of the people here. It’s a system that works. Look at us!

Well, what if this is not the best solution; what if the view we draw from the circumstance of our own society isn’t broad enough for us to see the entire picture; what if the answer here, even though the rate of infant mortality for children under five is excessively high, is nothing needs to change at all.

It is found that most developed countries are fortuned with such incredible health services and facilities that below 1% of children will die under the age of five. This is tribute to the wonderful medical research, advancements and services available.

What may not be taken into account though is that for mothers and families for whom this tragedy does occur the psychological impact today is often profound. It’s not uncommon for parents to suffer long-term implications such as depression and never fully recover; also impacting the lives of all those related.

Interestingly, for indigenous Mentawai, a society with a rate of infant mortality for children under five more than twenty times higher, the impact is not relative. In fact signs of any long-term effects on mothers or their families are non-existent. There is a period of grieving, termed a ‘crying’ period, but after this is concluded – which is marked by a ceremony releasing the spirit from the family home (Uma) – they appear to move on with life in much the same way as prior to their loss.

This is not suggesting the Mentawai value life any less than we or any other people do, absolutely not, and nor is there intention to criticise or question an approach that has proven successful in other parts of the world, or perhaps even in other – more developed – areas of Mentawai.

What this observation indicates though is that – with very little increase in health services and the availability of modern medical facilities within this remote region – their expectations have not been altered; they’ve maintained a realistic understanding for their circumstance and continue to deal with these deaths in the way they’ve long become accustomed.

A short video providing some insight into the Mentawai perspective:

Sure it is an extremely high rate of infant mortality when comparing to standards of a developed world, but for a community that compares only to itself it is in fact neither high nor low, it just is.

So I guess my concern, which I’m now realising as I explore these thoughts, is to what depth we actually consider the complexities of each individual community’s circumstance before proceeding to introduce such fundamental change to the systems and processes they’ve developed over a long period of time.

Are we considering the possibility that, if the circumstance of helping to improve the lives of indigenous peoples involves introducing foreign standards that alter a people’s psychological makeup and expectations away from that which they know and trust, we might actually be doing more harm than good?

Please, if you have an opinion on the topic – whether for or against – I’d be most interested to hear your comments. My apologies if you’ve found this offensive in any way. I’m really just trying to make sense of it myself. Thanks.

The project is at a stage where I’ve begun contacting and presenting to those I hope can help take it that next step toward release. Which is extremely exciting. Interestingly, I’m observing that people are generally really busy. Meaning that for many opportunities I await response.

Admittedly I’m not as aggressive in pushing for people’s time as I perhaps wonder whether I should be, but, well, it just seems strange that after not having rushed through the past years of this process myself, that I would suddenly feel obliged to pressure others into doing so. But then, how long are you to wait before a follow up is considered courteous rather than pestilent. Or is it that, in today’s world, to be hounded is an expectation and anything less indicates ignorance to understanding the system and leaves you falling behind. Hmm.

Moving on, a number of people have had the time to watch or listen and, of these, the response has been great. Almost all are now involved in the project in one capacity or another. Including the wonderfully talented David Kahne, who is to compose the film’s musical score. A number of other accomplished artists and (personally) admired persons have also been approached regarding the film and foundation and, whilst I can’t confirm any movements just yet, it’s fair to say that the project is (slowly) moving closer and closer toward reaching its goal. I’ll expand on these developments soon.

In the meantime, do enjoy a selection of photos taken with the indigenous Mentawai tribal community or, if interested in a personal insight into how a surf-driven venture to Mentawai evolved to become this project, have a read of this article recently featured on Coastal Watch. Cheers.

|

© Copyright Roebeeh Productions 2017 |